ABANDON IN PLACE

Amid the celebration of #Apollo50, considering the price of the first steps on the moon

July 18, 2019

Quillette.com

By Craig Colgan

The sun burns down through a forever sky on a sweaty Florida morning. The long deserted, circular concrete slab just steps from the Atlantic Ocean is wider than an American football field. Today, it hosts just two visitors: Someone with a very intimate connection to this place, who has agreed to serve as my tour guide. And me. That’s it. Somehow, this space seems to expand in all directions, across the wetlands to the immediate west and out to sea to the east. And then somehow vertically for miles. Up, up, up. To forever.

Dominating the space is the looming, four-post, 25-foot-high pedestal in the center of the slab. It supports a platform with a wide, circular opening to the sky. A few other items are strewn about amid blowing sand and random scrub vegetation. Two heavy, angled metal structures, neglected and alone across the slab at the edge, resemble skateboard ramps. These turn out to be rocket exhaust flame deflectors. Nearby are the two launch pads on which the moon rockets once stood. But this morning, except for the occasional squawk of the floating gulls above, Cape Canaveral Air Station’s Launch Complex 34 is completely silent. For a few years in the 1960s, it was the most advanced rocket launch facility on the planet. Today it is deserted and rusting.

My companion this morning knows a lot about this place. The tall launch service structure is long gone, as are the hundreds of people who worked at LC-34, and on all the successful launches here. In 1967, because of what happened here two-and-a-half years before the first moon landing, the whole country had to stop and decide what to do next. The tour guide’s father was absolutely going to go to the moon one day. Because on that very bad day, spent right here, more than 200 feet in the air on top of a rocket that stood on that pedestal, my companion’s father and his crew mates were trained and ready to fly away on a mission in advance of the one that landed three other men on the moon.

Launch pedestal and flame detectors at Launch Complex 34, long abandoned, at what in 2020 would be re-named Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

Between July 20, 1969, and December 14, 1972, 12 Americans walked on the moon. Describing the remarkable and inspiring and fascinating how is usually the focus of books and documentaries. The hardware side: A spacecraft to fly to the moon and back in. A second vehicle, which would fly down to the moon and land. Add to these, hundreds of innovative challenges met and insights revealed and necessities invented and perfected and refined. In a hurry. Large and small. Starting with the small miracle of a guidance computer which could navigate throughout the trip. NASA also had to learn how to locate and then find another spacecraft, a process called rendezvous. Then the two spacecraft had to be able to link and fly together. Several astronauts flailed about on multiple spacewalks before NASA finally figured out that challenge. And the moon venture would require an entirely new generation of rockets. These were flown unmanned, at first. Finally, the 363-foot moon rocket was ready for humans. Two missions of three-man crews flew to the moon, on perfectly executed but quite risky orbiting and near-landing practice missions. (Of course, every mission was “risky.”) Then two of the three Apollo 11 crew members ventured the final few thousand feet, landed, planted the American flag, collected some rocks, had a call with the President of the United States, and were watched by 600 million people.

The why is often misunderstood. The vigorous young president inaugurated in January 1961 decided the country needed a new, high-tech narrative. John Kennedy would provide it. And that’s the reason. Full stop. Everything else is detail. The new president used the rhetoric of the Cold War—the communists might weaponize space!—to look bold and modern and decisive. Especially after the Bay of Pigs disaster. We will beat the Soviets to the moon. We will control space, or so went the argument, and forever protect it from the Evil Empire. Which was, in fact, truly evil. America ate it up. So did the rest of the free world. The accomplishment certainly did stand alone, outside of its justification, flimsy or otherwise. Nevertheless, few bothered to ask: Was there to be some sort of award ceremony or official presentation that would make clear the first nation to the moon suddenly possessed some capability to destroy its rival by raining warheads from space? Or some protection from same? The loser nation was apparently expected to surrender its warheads-raining capability honorably. Sort of a silver medal at the Moon Olympics.

The tone was set in 1957. The Soviet launch that year of the first satellite—an oversized basketball-shaped globe that could send back audio beeps and do nothing else—freaked out much of America, the political establishment, and the media. The new president needed to show his administration was tough enough to reply. The problem: In private, the new president freely admitted that he didn’t really care much about space. Recorded meetings in the White House have him saying precisely that. After making a couple of passionate speeches imploring the country to join his quest to go to the moon by the end of the decade, Kennedy worried and ranted to his advisors about how much it would all cost. His Cold War cold feet even led him to speak publicly about the feasibility of joint moon missions with the Soviets. All of this because even the new president himself found such a task too difficult to manage. But the president changed his mind. He was convinced by what he saw of the project’s massive new hardware and its powerful capability. He even took a trip to a then very busy pad 34. Witnesses said Kennedy’s near-giddy reaction that visit and another to a Saturn engine test-firing dispelled any doubts he still entertained about what would become the largest successful rocket in history.

But three years after beating the Soviets to the moon, America simply stopped returning. The Lyndon Johnson administration set the Apollo program funding reduction in motion, even before the first moon landing. His successor, Richard Nixon, was wary of space. NASA knew perpetuating the man-in-space project was likely doomed. Ultimately, several planned missions ended up canceled. Nevertheless, NASA continued to innovate in its final missions through 1972. The moon missions became increasingly ambitious. The landings became more precise. The equipment improved. Surface experiments and activities became more complex. The astronauts roamed further and stayed longer. They actually drove a damn car on the surface of the moon.

When it was over, what did mankind gain and realize and learn? A lot, it turns out. About space flight itself, of course. About the nature of the moon and its history. And about the Earth, surprisingly, and its fragility and value. Apollo itself inspired hundreds of spin-offs in medicine, water quality, imaging, communications, entertainment, transportation, agriculture, household products, cameras, vacuum-sealed food. The seismic shock absorbers on California’s Bay Bridge and on London’s Millennium Bridge were created by the same company that built similar devices for the Saturn V. And many others. Including material used in firefighter protection developed by NASA after a shocking tragedy right here on Launch Complex 34.

•

The more famous launch pads, 39A and B, used for the moon missions, are just up the road from Launch Complex 34. SpaceX renovated 39A. Pad 34 launches were viewed from a concrete blockhouse a mere 900 feet from rockets a class below the giant Saturn V. The power of which forced sane humans to watch from fully three miles away.

“I feel peaceful when I am here,” says my LC-34 tour guide. Who is not a real tour guide. But she does work at Kennedy Space Center. Where her father trained. She’s also a mom. Her son needs her on her phone. She sits in the car and calls him. I wander. The breeze is firm from the ocean probably not 200 feet away. On that Friday afternoon in January 1967, it all happened so quickly.

That rocket that day was locked down on the pedestal I walk under. The tall, orange service structure surrounded it. The first three-man Apollo crew was tucked into their new spacecraft. The complicated hatch shut tight, pressurized with 100 percent oxygen, and disconnected from all but internal power, for a series of tests run on what was then a brand new machine. Their mission, set to launch in February 1967, would be to fly this new vehicle in Earth orbit for two weeks simply to ensure it worked. But, for months, the project was beset by continual problems. That afternoon was no different.

The test was being monitored from the blockhouse right next to the pad. The audio reveals continual frustration among the astronauts because of communications problems. Then, suddenly, chaos. Shouting and screaming. Over the loop: “We’ve got a bad fire!” “We’re burning up!” Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee perished in moments in the conflagration, begun by some unknown wiring short, and fed by the pure oxygen. Smoke and heat and that disastrously incomprehensible hatch design made rescue impossible. Death came from smoke inhalation, NASA says, as the fire did quickly burn itself out. The country was appalled. Mostly by the shoddy work on the spacecraft from the contractor that built it. But also by NASA’s incomprehensible management failings. Two years of improvements to the design followed major investigations, first by NASA itself, then by a furious Congress. These investigations found that, even if this first spacecraft had managed to leave the ground, it was most likely doomed for various other reasons. The program would never be the same. The new spacecraft was better, more reliable, and safer. The hatch was redesigned. The oxygen mix was altered. In interview after interview, those who were there and those who ran NASA at the time agree: NASA would not have reached the moon without that brand-new spacecraft. And there would have been no brand-new spacecraft without the fire.

•

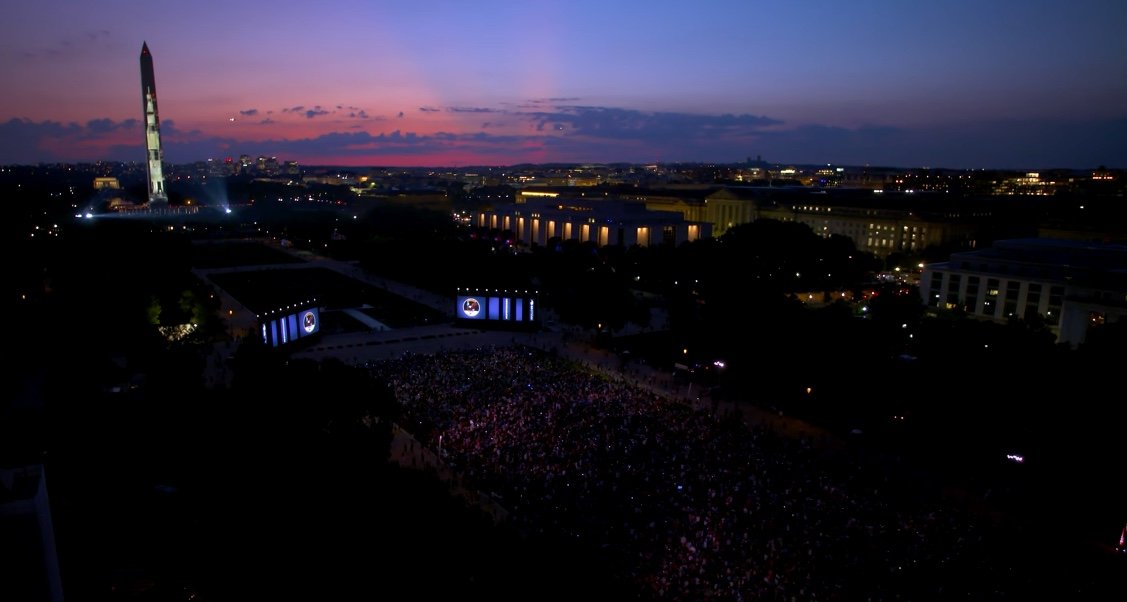

Saturn V launches from the Washington Monument, 2019.

I took my 12-year-old son this week to the National Archives for a screening and panel discussion with the director of the acclaimed new Apollo 11 documentary. After which we walked outside onto the National Mall in the dark and what we saw made me temporarily light headed. Amid a host of activities in Washington this month to mark the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing, an image of the colossal Saturn V moon rocket has been projected on the side of the Washington Monument after dark. For a few moments, standing there in the dark, gaping up at this image on the marble, it came alive somehow — video “steam” was vented out of the rocket, just as happened after the real rocket was fueled. Several nights later, in a multimedia spectacle with lights and video and music, we watched as that rocket launched. In front of thousands. It is not easy to explain how this all felt. The experience was surprising and teary and exuberant and uniting. I hugged my son. He seemed to get that this all is about something important.

Saturn V stars in a multimedia show on the National Mall, July 2019, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission to the moon.

It is remarkable that the Apollo history remains such a powerful tale to so many people. Social media groups proliferate about Apollo and NASA and even various individual pieces of the story. The vehicle that landed on the moon, called the lunar module, has its own Facebook group. And there are new books and documentaries everywhere. The big news for space geeks is that the “consoles” from the Apollo mission control center in Houston have been remodeled and re-installed. Not to be re-used. But to be looked at and sat in front of and photographed by visitors to what has become a museum. They look exactly as they did during the Apollo missions. Chasing the Moon, by noted documentary director Roger Stone, ran on The American Experience series on PBS over three nights earlier this month. It will likely be remembered as the greatest moon landing documentary, and perhaps the last with the participation of various controllers and astronauts of the era. (Though wild-man astronaut Buzz Aldrin, a PhD who walked on the moon as part of Apollo 11 and once punched out a moon-landing denier, is still around, living up to his first name. buzzing around wearing shirts with the command, “Get Your Ass To Mars.”)

NASA has always claimed that 400,000 people contributed to the moon landing. I was a child in the 1960s, and I embraced Apollo as the adventure of all time. The Aeroquip Corporation was based in my blue-collar hometown of Jackson, Michigan, and I remember it most as a sponsor of local softball and bowling teams. Parents of several of my friends worked at the plant. As best as I can recall, it manufactured mostly auto parts back then. But apparently it would occasionally branch out and is first in this alphabetical list of major subcontractors of Boeing for the Saturn V. The product listed is “couplings, pneumatic, and hydraulic hoses.” Ask me if I feel a little proud of my hometown. Go ahead.

On this breezy Florida day, steps from the ocean, wandering the ruins of this abandoned piece of the busy and important rocket city, I stroll around the looming rocket stand. Eulogized on a plaque here is the father of my very kind tour guide on this day. Her father and her father’s two fellow astronaut crew mates were ready and eager to fly away from this spot, on that Friday evening, on what would have been Apollo 1, the first trip into space for the Apollo spacecraft. It never made it. Their spacecraft and the men who built it failed them as egregiously as could be conceived. But changes made over the months to the safety of myriad systems ensured the program could go on, and so that is why there is an #Apollo50. Spray painted on the side of the main, aging structure are the words “ABANDON IN PLACE.” A metaphor for those three lives. The yawning, circular, concrete plane is eery and vast, several remaining half walls standing alone, over there two rocket flame deflectors, amid beach vegetation poking through the slab, all giving off a strange, Cold War Stonehenge vibe. But considering each of these odd objects up close across this enormous, flat, horizontal is not how the truth of the place is best revealed. Stride to this long left-behind launch pad’s heart and center. Viewed from directly under the open, circular rocket pedestal, the sky seems bluer. And you are floating. Stare up. All the way up. The sky is forever.

Craig Colgan is a Washington-based writer. A version of this piece appeared in Quillette. NASA’s Apollo 1 site offers investigatory reports, photos, crew bios, history, etc.